Comedy, Tragedy, and Radio 3.

/

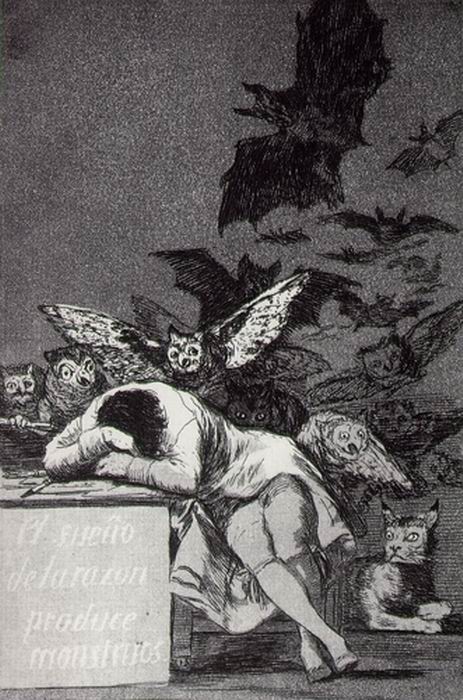

I will be blithering about comedy this weekend, as part of BBC 3's Free Thinking Festival, if that’s the kind of thing that scratches your scrotum or tickles your cervix. There's lots of good stuff in the festival, but my event will be a gory battle to the death between Tragedy and Comedy, that will take place live in The Sage, Gateshead (near Newcastle), and be broadcast on BBC 3's Nightwaves some time later (not sure when). Wearing the black hat and jackboots of tragedy, Professor of English Carol Rutter and comedian and classicist Natalie Haynes. Wearing the white hat and extremely long floppy shoes of comedy, passionate comedian Janey Godley and me. It's ticketed, but free.

More details on that, including how to get free tickets, here.

The problem of comedy has certainly furrowed my mighty brow this month. “Reality Is A Bananaskin On Which We Must Step” addresses that very subject, in the latest issue of A Public Space. For those of you too lazy to click through to the whole thing, I’ll sum it up for you in a line:

The relationship of a rock to its mountain will never be funny, because the rock does not believe it is the centre of the universe.

Meanwhile, let me recommend a book, or at least 50% of a book: I am halfway through Red Plenty, by Francis Spufford, and so far it’s the most enjoyable thing I’ve read all year. A splendid novel about Soviet economics in the 1950s, it reads like the satirical science fiction of the wonderful Strugatsky brothers. (They wrote the charming Roadside Picnic, which Andrei Tarkovsky filmed, in far bleaker form, as Stalker.) But it’s all true. A superb novel of ideas, deeply researched, deeply felt, deeply enjoyable, if it stays this good to the end it will be my novel of the year… I‘ll post a final verdict when I’m done.